This section will cover different types of databases and will incorporate some take-away from this YouTube video.

Relational Databases (RDB)

Tables with rigid schemas, ACID transactions and the declarative power of SQL. Oracle, Microsoft SQL Server, MySQL and PostgreSQL still run the bulk of the world’s transactional workloads.

Pros

- Mature, battle-tested ACID guarantees – transactions, constraints, backups all “just work”.

- SQL remains the most expressive and portable query language.

- Huge ecosystem: ORMs, BI tools, cloud services, battle-hardened DBAs.

- Absorb new paradigms quickly: JSONB columns (PostgreSQL 9.4+) killed much of the MongoDB argument; the pgvector extension and Postgres 16’s native indexing give first-class vector search in the same engine

Cons / Cautionary notes

- Vertical scaling is still easier than horizontal sharding.

- You pay an up-front schema tax (changes require migrations).

- Write-heavy, schemaless or time-series data can need careful tuning.

Key-Value Stores (KVS)

lookup tables: give me key → get value. Redis, Memcached, Dynamo, FoundationDB (in its raw layer).

Pros

- Blazing performance, especially in-memory.

- Linear, almost trivial horizontal scaling.

- Perfect for caches, session stores, idempotency tokens, rate-limit counters.

Cons

- No secondary indexes, joins or ad-hoc queries – you must know the key.

- Data modelling beyond “cache” gets messy fast.

- Persistence and recovery semantics vary; careless use leads to subtle data loss.

Take-away from the field lesson

The guy from the video once used Redis as the main database for an IoT project, thinking its simplicity was a benefit, especially for SD card-based devices with limited write cycles. But the project quickly ran into issues:

- Complex state management became messy with Redis’s data structures.

- Unreliable power/network meant lots of corner cases, and Redis wasn’t great at data persistence or recovery.

- Bugs emerged that would’ve been easily avoidable with a proper SQL database.

Lesson: Never use KVS for anything beyond caching.

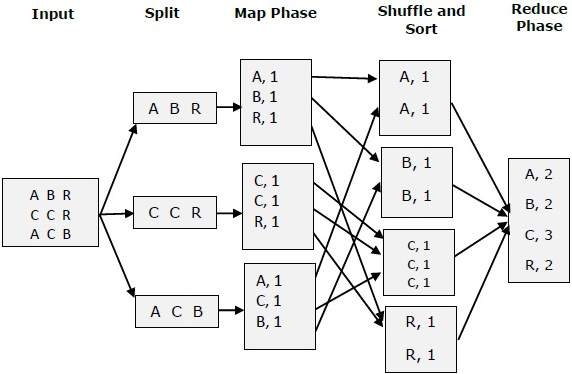

MapReduce / Hadoop

A distributed computing paradigm, not a traditional database, used for processing large volumes of data in parallel across clusters.

Pros

- Handles massive datasets well.

- Fault-tolerant, distributed by design.

- Suited for batch analytics on unstructured data.

Cons

- Complex data modeling (requires understanding partitioning).

- Limited query capabilities compared to SQL. Writing even simple aggregations used to mean hundreds of lines of Java.

- Eventual consistency in many systems.

- Latency measured in minutes or hours – unsuitable for interactive workloads.

- Spark, Flink and serverless query engines (BigQuery, Snowflake) displaced the DIY MapReduce stack; many shops have decommissioned Hadoop clusters .

Take-away from the field lesson

Even Google dropped MapReduce internally while the rest of us were still learning Hive. Once SQL-on-Hadoop (Hive, Presto) arrived, people realised they only ever wanted the SQL layer anyway.

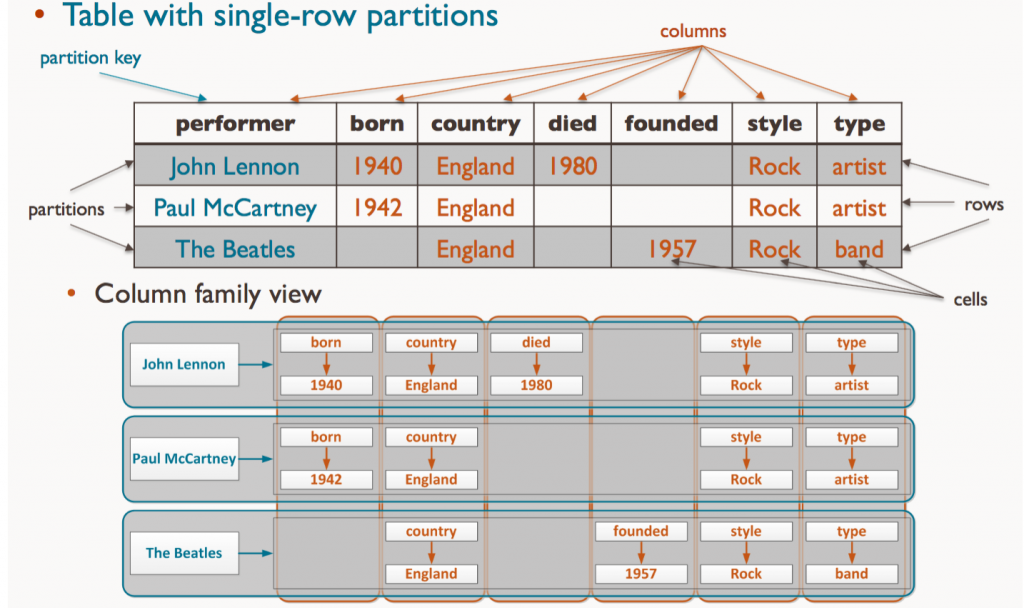

Wide-Column Stores (Bigtable family – Cassandra, HBase, ScyllaDB)

In a relational database, every row in a table has exactly the same columns — even if some are NULL, the schema is fixed.

But in a wide-column store (like Apache Cassandra, HBase, or ScyllaDB), each row can have a different set of columns. Think of it like:

Row 1 → { user_id: 1, email: "a@example.com", phone: "1234" }

Row 2 → { user_id: 2, address: "xyz street" } ← no email, no phone

Row 3 → { user_id: 3, email: "b@example.com", login_count: 5 }

Each row can omit fields that don’t apply to it — and this is by design, not an error.

It’s excellent for massive write throughput and time-series–like data.

Pros

- Write-optimised, eventually consistent, masterless clustering.

- Unlimited “wide” columns let you model semi-structured or time-series data without joins.

- Cassandra 5.0’s new Storage-Attached Indexes (SAI) finally give flexible secondary indexing.

Cons

- Data modelling is query-first – get it wrong and you rewrite tables.

- Secondary-indexing, ad-hoc queries and aggregations remain weaker than SQL.

- Harder operational learning-curve (tuning compaction, partition keys, repair).

Take-away from the field lesson

The guy’s team used a wide-column DB (likely Cassandra) for scraped web data; the schema-on-write freedom produced a table with thousands of semi-random column names that nobody could remember. Business folded two years later. Flexibility without discipline hurts maintainability.

Document Databases (MongoDB, Couchbase, Firebase Firestore)

Stores data as JSON or BSON documents. A common NoSQL type used in modern web applications.

Pros

- Flexible schema (good for iterative development).

- Natural fit for object-oriented programming.

- Good for hierarchical or nested data.

Cons:

- Absence of schema ≠ absence of structure – sooner or later you need rules, migrations and multi-document joins.

- Schema flexibility can lead to data inconsistencies.

- Performance can degrade if not indexed well.

- Heavy write lock-contention and index bloat if you treat it like an RDB.

Take-away from the field lesson

MongoDB’s “NoSQL will replace SQL” marketing convinced many execs, but production incidents (data loss, inconsistency) sobered them. Once Postgres/MySQL gained high-performance JSON, much of Mongo’s edge vanished.

Vector Database (Pinecone, Weaviate, Qdrant, Milvus)

Designed for similarity search across high-dimensional vectors—commonly used in AI/ML, recommendation engines, and semantic search.

Pros

- Optimized for nearest-neighbor search.

- Essential for AI applications (e.g., embeddings from LLMs).

- Can integrate with traditional metadata filtering.

Cons

- Niche use case (not for general data storage), vector similarity is rarely your only query.

- Newer ecosystem; still maturing.

- Difficult to scale and manage if not purpose-built.

Take-away from the field lesson

The guy tried to build an e-commerce search that also needed inventory rules, pricing tiers and geo-filters; juggling a vector DB for embeddings plus relational filters elsewhere became “code from hell.” A single engine that can mix embeddings and standard predicates in one query is far simpler—which is exactly where RDBs are heading.